| |||||||

Jochen Hemmleb: Mallory & Irvine Research Expedition, 1999

In spring 1999, an international search expedition travelled to Mount Everest in an attempt to rediscover the "English dead" found by Chinese climber Wang Hongbao in 1975 - Mallory or Irvine. It was hoped that the body was still carrying one of the cameras the climbers had taken on their attempt. The films of these cameras, frozen by the cold at 26,500 ft., could yield evidence of how high Mallory and Irvine had got on their summit bid.

In spring 1999, an international search expedition travelled to Mount Everest in an attempt to rediscover the "English dead" found by Chinese climber Wang Hongbao in 1975 - Mallory or Irvine. It was hoped that the body was still carrying one of the cameras the climbers had taken on their attempt. The films of these cameras, frozen by the cold at 26,500 ft., could yield evidence of how high Mallory and Irvine had got on their summit bid.The 1999 expedition was only the second attempt ever at searching for the missing climbers. A first attempt, instigated in 1986 by American researcher, Tom Holzel, and British mountaineering historian, Audrey Salkeld, failed due to bad weather and the death of a sherpa before reaching the actual search area on the mountain. Over the years after 1986, several parties carried forward the idea of another search, namely this author and Briton Graham Hoyland, a BBC employee and grand-nephew of Mallory's friend and expedition colleague, Howard Somervell.

Foundations for the 1999 expedition were laid in summer of 1998, when American Larry Johnson, them marketing director of a publishing company in Harrisburg, PA, presented this author's research concept to mountain guide Eric Simonson. Simonson counts among the most experienced organizers of Everest expeditions, besides having a strong interest in mountaineering history. At the same time, the BBC consented to Hoyland's film project about the search, and after overcoming several organizational and logistical hurdles both parties joined forces. Financial backing was provided by TV companies BBC (GB), PBS/Nova (USA), and ZDF (D), as well as outdoor equipment companies like Lowe Mountain Sports, Mountain Hardwear, and others.

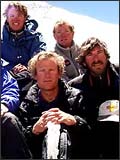

The team included leader Eric Simonson, five high-altitude climbers (Conrad Anker, Dave Hahn, Jake Norton, Andy Politz, Tap Richards), expedition doctor Lee Meyers, and myself as historian. They were accompanied by a six-member TV crew: Graham Hoyland, producers Peter Firstbrook (BBC) and Liesl Clark (PBS), cameramen Ned Johnston and Thom Pollard, and sound engineer Jyoti Rana. The expedition was supported by eleven sherpas.

The Mallory & Irvine Research Expedition 1999

Standing (f.l.t.r.): Lee Meyers, Conrad Anker, Andy Politz, Dave Hahn, Thom Pollard

Jake Norton, Tap Richards, Eric Simonson; kneeling: Jochen Hemmleb

(not shown: Graham Hoyland, Larry Johnson)

© Archive J. Hemmleb, Idstein/Germany

The expedition left Kathmandu (Nepal) on March 23, 1999, and reached Base Camp on the Tibetan North Side of Everest six days later. On the mountain they followed the classic route taken by the British expeditions before World War II, via the East Rongbuk Glacier, North Col and North Ridge. Camp V was established at 25,600 ft. on April 19, serving as launch pad for the first search.

The Finding of George Mallory, May 1, 1999

The search team started their ascent from Camp V at 5 a.m. on May 1, reaching Camp VI on the North Face at 26,900 ft. in five hours. After half an hour of rest, I guided them over radio from Base Camp to the search area, a basin measuring 200 x 200 m west (right) of the 1975 Chinese Camp VI, from where Wang Hongbao had found his "English dead". At 10.45 a.m., Norton reported finding an oxygen bottle from the 1975 Chinese expedition - the search team was in the vicinity of the camp, and thus right on track.

The climbers now spread out into a grid pattern. Hahn stayed near the ill-defined rock rib indicating the location of the Chinese camp; Richards and Norton investigated the broad chute to the right of the rib; Politz climbed to the upper rim of the basin, into the cliffs of the Yellow Band; and Anker descended to the lower rim, where the basin breaks off in a series of steep crags.

During the first 45 minutes of the search, the climbers discovered three or four victims from more recent expeditions. From this it became apparent how the search area acted as a catchment for anything or anyone falling down the North Face from the Northeast Ridge below the First Step.

Anker was returning from the lower western rim of the basin, when he spotted a blue-yellow object fluttering in the wind. He traversed over for closer examination. As he happened to look over his right shoulder, he suddenly saw "a patch of white, that was whiter than the rock that was around and also whiter than the snow." It was another corpse - but not from recent times. A bleached-out heel, a nailed leather boot, natural fibre clothing - all this indicated that it must have been there for a long time. It was 11.45 a.m.

The body was lying face-down on a sloping ledge, head pointing uphill. The upper torso was firmly frozen into the gravel that had accumulated around it over the years. The clothing consisted of several layers of cotton, silk, wool, flannel and canvas. The head was covered in a fur-lined motorcycle leather helmet, the right leg still wore putties, three pairs of woollen socks, and a nailed leather boot. Most of the clothing on the back was missing, shorn away by the wind. The exposed skin was bleached white by the sun, looking like marble. Only where it had been covered the skin showed a yellow-brown colour, the bare hands were almost black in places. Large parts of the buttocks, right thigh, and the abdominal cavity had been pecked by birds.

Mallory's body shortly after its discovery on May 1, 1999

© Tap Richards/Mallory & Irvine Research Expedition 1999, from "Ghosts of Everest"

Everything pointed to a fall. The right tibia and fibula were fractured above the boot top, the lower leg bent at a sharp angle. The right elbow was either broken or dislocated. Closer inspection revealed cuts, abrasions and bruises along the right side of the body. The torso was tangled in a length of broken climbing rope. The rope had squashed the rib cage and probably broken some ribs on the left side. The posture of the body, with its arms stretched out over the head, looked as if the climber had tried to self-arrest. But who was it?

We had always assumed that if any body was ever to be found, it was Andrew Irvine's - largely because it had been his ice-axe that was found on the ridge above the search area in 1933. The team then searched the body's clothing for any camera, personal effects and means of identification. Eventually Norton turned over a piece of the collar and a clothing label became visible. Norton looked hard, then paused... "Wait, this says 'George Mallory'!"

Investigating Mallory was difficult. The ground was frozen solid, and the location was poised on a 30-35° slope. Immediately below was a huge drop-off, from above it was threatened by stonefall. The search team had taken off their oxygen sets in order to move around more freely - which meant hard physical work in the rarefied air at 26,750 ft.

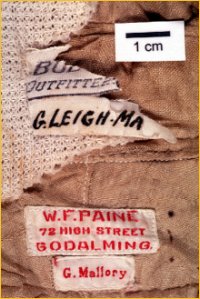

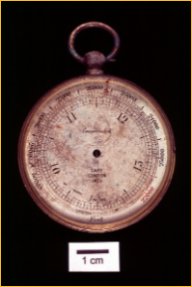

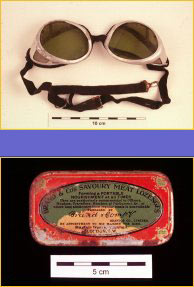

After one hour they had scraped away enough of the frozen gravel to access the pockets on the jacket's chest and a pouch hanging around the neck. Inside they found a broken altimeter, a tin of meat lozenges, a matchbox, a penknife, a tube of petroleum jelly, a spare glove, and several smaller items (pencil, safety pin, nail scissors). In one of the chest pockets the team discovered a stack of letters and notes, wrapped in a monogrammed handkerchief, "GLM". They recovered samples of the clothing and cut a piece of tissue from the forearm for DNA analysis.

Mallory did not wear an oxygen set. He must have discarded the apparatus before the fall, as the connecting piece between the oxygen mask and leather helmet was found tucked away in one of his pockets. Also found in a pocket were Mallory's goggles. No camera or film was found.

Mallory's altimeter, snow goggles, and tin of meat lozenges

© Rick Reanier/Archiv J. Hemmleb, Idstein

After three hours of investigating the body and documenting the find, the search team buried George Mallory by covering him with a protective layer of rocks. Afterwards, Politz read the funeral service: Psalm 103, which was given to the expedition by the Bishop of Bristol in accordance with the wishes of Mallory's surviving relatives. At 4 p.m. the climbers left for Camp V, arriving there at 5.30 p.m.

"All these events, of course, I couldn't know in the afternoon of May 1st. Sitting twelve miles away behind the telescope and listening to the silence on the radio, I was bound to wait - until at 6 p.m. Dave Hahn came over the air from Camp V, finally bringing the message of confirmation I'd been hoping for all day (or maybe eleven years...): 'It was Conrad with the big day... and Jochen, you are going to be a happy man!'

Stepping outside our 'research tent', I dropped to my knees in front of the big mountain, all the anticipation, tension and relief finally set free in one exuberant cry of joy...

It was the greatest moment of my life.

![]()

| Proud Climbing Team of the Mallory & Irvine Research Expeditions: | ||