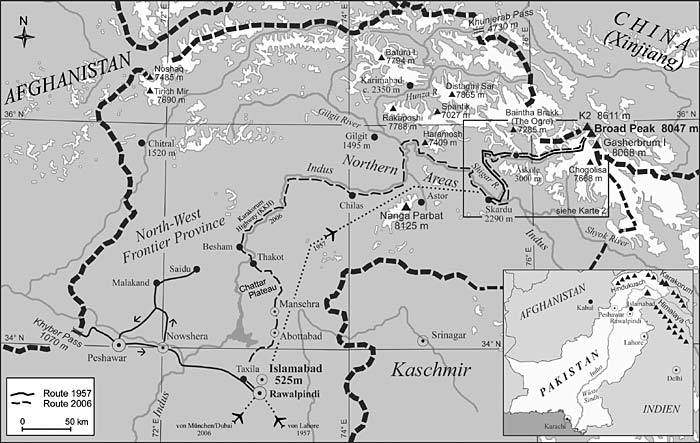

On the trails of Hermann Buhl's last expedition & Study of glacial recession in the Baltoro Range, Karakoram (Pakistan)

Part I — History

Broad Peak, located some 10 kilometers SE of K2, is the 12th highest mountain in the world. It was first discovered and sketched during William Martin Conway's Baltoro reconnaissance expedition in 1892. Various measurements of the mountain's altitude over the next 34 years established the now commonly used figure of 8,047 m (26,402 ft.).

Although the International Himalaya Expedition (IHE) of 1934, led by Swiss geologist and geographer Gunter Oskar Dyhrenfurth¹, found the W-Spur a suitable route of ascent, it wasn't until 20 years later that a first attempt to climb Broad Peak was undertaken; climbing activity on the 8,000-meter peaks the Baltoro Range had previously focused on K2 (American expeditions of 1938, 1939 and 1953) and Gasherbrum I (IHE 1934 and French expedition 1936).

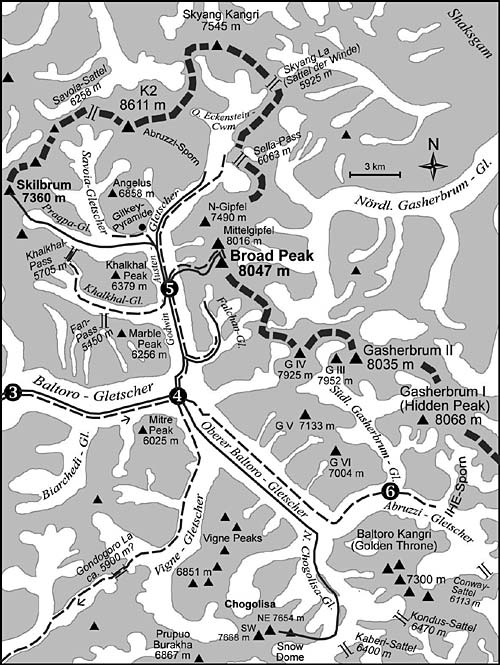

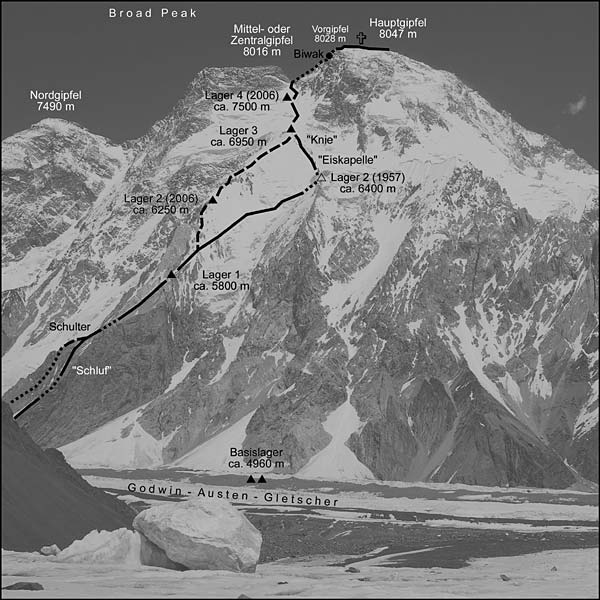

Map 4: Broad Peak, 1957 with first ascent route (solid line); 2006 ascent (dashed line); hidden route (dotted line)

Karl Maria Herrligkoffer's² German-Austrian expedition of 1954 approached the W-Spur by an objectively dangerous line through its southern flank, eventually reaching the crest at c. 6,400 m (21,000 ft.). Ernst Senn and Michl Anderl later gained an altitude of c. 7,200 m (23,620 ft., according to Herrligkoffer. Photographs suggest 23,000-23,300 ft.), before the expedition — a fall attempt — was turned back by the onset of winter storms.

¹ Father of Norman G. Dyhrenfurth, leader of the 1963 American Everest Expedition.

² Leader of the successful first ascent of Nanga Parbat in 1953, during which Hermann Buhl made his legendary solo bid for the summit.

The first ascent — a milestone in climbing history

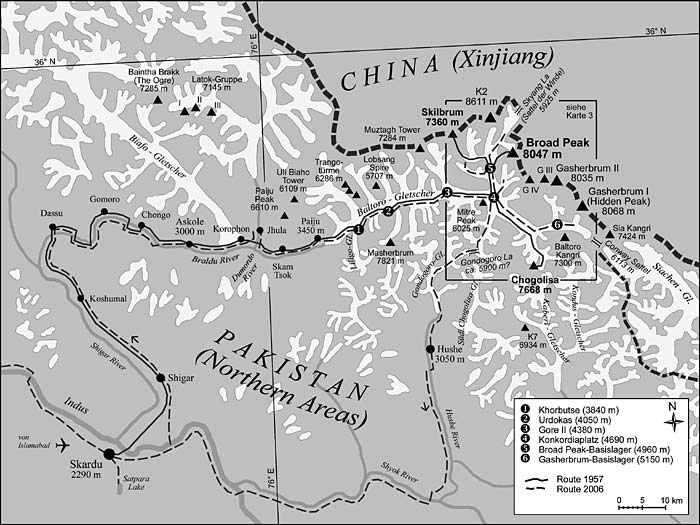

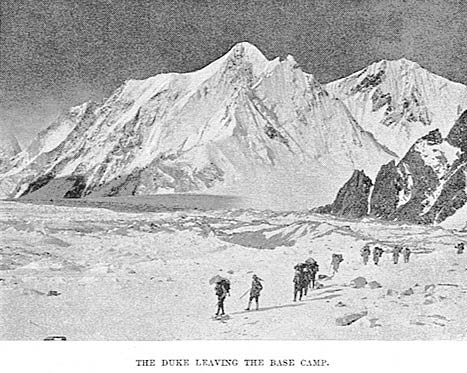

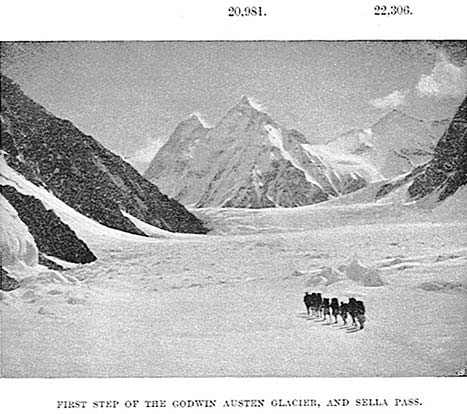

Broad Peak was first climbed on June 9, 1957, by an Austrian team of four: Marcus Schmuck, Fritz Wintersteller, Kurt Diemberger, and the legendary Hermann Buhl. Their ascent is regarded as a milestone in climbing history: For the first time one of the world's fourteen highest peaks had been climbed without the aid of native high-altitude porters. Although porters carried the expedition's equipment to Base Camp on the lower Godwin Austen Glacier, the climbing team reconnoitered and prepared the route along the W-Spur on their own, establishing three high camps and using a minimum of fixed ropes. They also climbed without supplementary oxygen.

A first summit attempt on May 29 got Wintersteller and Diemberger to the foresummit at the northern end of the kilometer-long summit ridge. Although the foresummit is a mere 19 meters (62 ft.) lower than the main summit, the expedition returned once more to the mountain to complete the ascent. Nowadays, many parties remain content with the foresummit — but from a historical and topographical view, this should not be regarded as an ascent of Broad Peak!

After success on Broad Peak, the team — which had been beset by personal conflicts — split in two. On June 19, Wintersteller and Schmuck climbed the highest peak in the Savoia Group west of K2, later named Skilbrum (7,360 m/24,148 ft.). The climb was done "alpine-style", i.e. the pair carried tent, sleeping bags, cooking equipment, provisions and climbing gear as if going for a climb in the Alps. They camped once on the way up and down, and used short skis for the ascent and descent.

There had been a few early predecessors of alpine-style climbing in the Himalaya and Karakoram — Alexander Kellas on Pauhunri (23,387 ft.) in Sikkim 1911 or Herbert Tichy's attempt on Gurla Mandata in Tibet 1937, to name but two. But it should take another 20 years before a new generation of mountaineers established small-scale expeditions and alpine-style climbs on the 8,000-meter peaks (e.g. Messner and Habeler on Gaherbrum I in 1975 or the British three-man ascent of Kangchenjunga in 1979).

Death of a legend

Buhl and Diemberger, on the other hand, went to attempt Chogolisa ("Bride Peak", 7,668 m/ 25,159 ft.) at the head of the Upper Baltoro Glacier. Climbing also alpine-style, the pair reached 7,300 m (23,950 ft.) on the East Ridge in six days before being turned back by a storm. During the retreat, going unroped, Buhl stepped onto a cornice and fell to his death (June 27). Diemberger fought his way back through gales avalanche-prone slopes and séracs, eventually arriving back at Broad Peak Base Camp 27 hours after the accident. A tentative search by the survivors proved fruitless.

A classic peak with future possibilities

The main summit Broad Peak did not see a second ascent until 1977. A Polish party had climbed the Middle Summit (a.k.a. Broad Peak Central, 8,016 m/26,300 ft.) in 1975, but three of the five summit climbers died on the descent.

In the years since then, Broad Peak developed a status as one of the "easier" 8,000-meter peaks, while at the same time it remained a testing place for modern, hard climbing: its North Summit (7,490 m/24,575 ft.) saw its first ascent in 1982 in a remarkable week-long tour de force by Italian soloist Renato Casarotto; in 1984, Poles Jerzy Kukuczka and Wojciech Kurtyka made an on-sight, alpine-style traverse of all three summits and descended the classic W-Spur. An international expedition made the first ascent of Broad Peak from the Chinese (E-) side in 1992, reaching Broad Peak Central. Mexican Carlos Carsolio opened up a direct variation of the W-Spur in 1994. And recently, in 2005, Kazakhs Denis Urubko and Serguey Samoilov made the first ascent of the mighty SW-Face, alpine-style. The long S-Ridge is still unclimbed.

Part II — Our 2006 expedition: On the trails of Hermann Buhl

Our 2006 expedition to the Baltoro consisted of Austrians Markus Kronthaler (leader), Dieter Antoni, Sepp Bachmair, Engelbert Obex, Peter Ressmann, Wolfgang Wörister, Gerald Zenz; and Germans Sepp Heigenhauser, Reinhard Keck, and I as writer/historian. It was our aim to commemorate the 50th anniversaries of the first ascent of Broad Peak and the death of Hermann Buhl on Chogolisa (both due in 2007) by attempting ascents and ski descents of both peaks.

On Broad Peak we followed the classic route by the West Spur. On June 19, Bachmair and Ressmann skied down the original 1957 route from Camp 3 (6,950 m/22,800 ft.). A first summit attempt on June 24 by Kronthaler, Bachmair and Ressmann failed in deep snow at c. 7,600 m (24,940 ft.); a second attempt by Antoni and Zenz was fouled by a storm at Camp 3.

At this stage, we were very impressed by the performance of the 1957 first ascent team, which had made each summit bid out of Camp 3, while nowadays many expeditions put in an additional Camp 4 at 7,500 m (24,610 ft.). After the two failed summit bids we abandoned our Chogolisa plans due to time constraints.

On July 5 Bachmair and Ressmann climbed in a single push from Base Camp to Camp 3, catching up with Kronthaler at Camp 2, who got there the previous day. Together they left for the summit from Camp 3 at 11.30 pm. Climbing behind a strong Spanish group and two other climbers they arrived at the notch between the central and main summits (c. 7,800 m/25,590 ft.) at 12.30 pm on July 6. Continuing ahead of his partners, Ressmann reached the foresummit at 5 pm and the main summit at 6 pm. Three Spaniards also summitted earlier the same afternoon, among them Dr. Jorge Egocheaga, who made a speed ascent (21 hours from Base Camp to the summit and return). On the descent, Ressmann met his partners, who had decided to bivvy in a crevasse at c. 7,950 m (26,080 ft.). Ressmann continued down to his ski cache at 7,500 m and skied down to Camp 3 by moonlight, arriving at 11.45 pm. The next day he skied to the base of the mountain.

After their bivouac, Bachmair and Kronthaler continued very slowly, not reaching the main summit until 3-3.30 pm on July 7. On the way down Kronthaler's strength gave out halfway between the top and foresummit. Through the night, Bachmair tried to support, drag and even carry his partner, but to no avail. Kronthaler died of dehydration and exhaustion at 6 am on July 8. Bachmair continued his descent to the notch, where he came across a Polish-Slowakian rope. One Pole, Piotr Morawski, gave up his summit bid and accompanied Bachmair down to Camp 3 (Morawski reached the summit solo the next day). Above Camp 3 they were met by Jorge Egocheaga, who, despite his speed ascent two days earlier, had immediately offered to climb back up again and help. He nursed Bachmair during the night and, together with two Argentineans, accompanied him down to base camp on July 9.

Our expedition extends our heartfelt thanks to Dr. Jorge Egocheaga and Piotr Morawski for their extraordinary efforts in helping Sepp Bachmair. The support we received from them and every other expedition on the mountain will be a lasting memory.

Part III — Study of glacial recession in the Baltoro Range

While the main focus of our expedition had been the ascent of Broad Peak and Chogolisa, I also explored the surrounding glaciers and undertook the following excursions:

- Falchan Glacier (1954 route to 5,000 m/16,400 ft.; 12 h round trip from BC, June 17)

- Upper Godwin Austen Glacier to Oscar Eckenstein Cwm (to c. 5,580 m/18,300 ft., June 20-21)

- Savoia Glacier (to c. 5,100 m/16,730 ft., June 30-July 1)

- Upper Baltoro Glacier and Abruzzi Glacier (to c. 5,250 m/17,225 ft., July 4-7)

Together with the approach from Payu, these excursions covered almost the total length of the Baltoro Glacier to its head below Conway Saddle (6,113 m/20,057 ft.; border to Kashmere) — 54 of 58 kilometers — plus 14 kilometers of the 20-kilometer Godwin Austen Glacier, the two main glacier systems of the Baltoro Range.

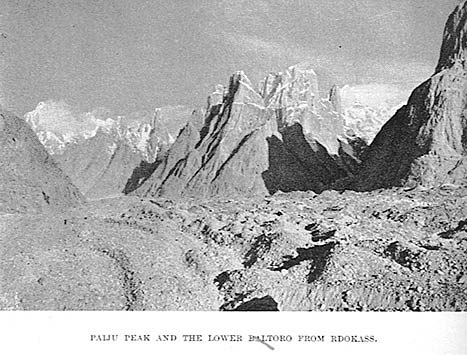

The excursions also retraced in large parts the route of the 1909 Karakoram expedition, led by Italian Luigi Amedeo di Savoia, Duke of the Abruzzi. This expedition was the third to penetrate the heart of the Baltoro (after the 1892 Conway reconnaissance and Eckenstein's attempt on K2 in 1902) and the first to provide a comprehensive photographic record of both the Baltoro-Abruzzi and Godwin Austen Glacier systems.

Retracing the 1909 route almost a century later provided an opportunity to study the changes the glacial cover has undergone since then — and the results gave a very instructive, sometimes visually dramatic, insight into the much-debated consequences of global warming.

(The historical images from the 1909 expedition were scanned from the contemporary account, Karakoram and Western Himalaya by F. de Filippi; London: Constable and Company Ltd., 1912)

Section A: Lower Baltoro Glacier (Payu-Concordia) and side valleys

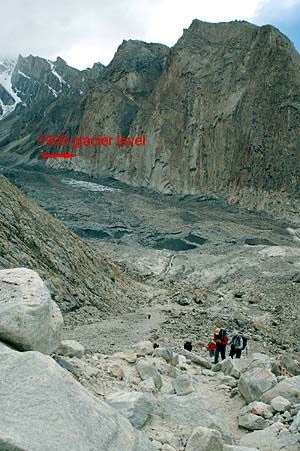

An overview of the Lower Baltoro Glacier from Urdokas, some 13 Kilometers upvalley from the glacier's snout, shows that the present level of the glacier surface is at least some 50 m lower than it had been in 1909. Also, the surface is now considerably smoother, showing fewer moraine hummocks.

The tributary Liligo Glacier, which joins the Lower Baltoro some 5 kilometers downvalley from Urdokas, has undergone the perhaps most dramatic change since 1909. The once prominent snout (height c. 150 m/500 ft.) has completely disappeared, and demarcations visible on the western valley flank indicate a loss of at least half of the ice's thickness.

The loss is less visible along the ice margins at Concordia, the confluence of the Baltoro and Godwin Austen Glacier systems, but the volume of the central ice flows between the medial moraines appears to be reduced.

Section B: Upper Baltoro Glacier, Abruzzi Glacier, and side valleys

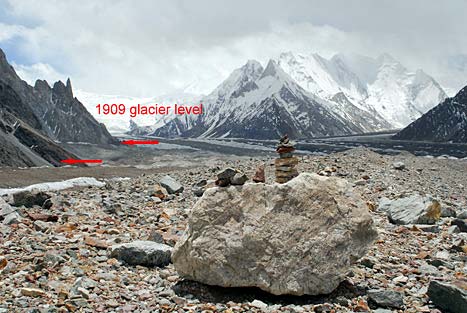

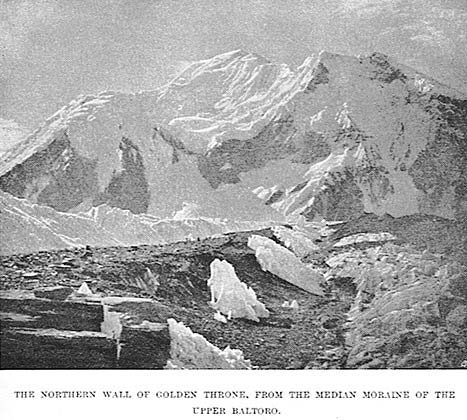

This latter observation is confirmed by images taken along the medial moraine of the Upper Baltoro Glacier towards Baltoro Kangri. In comparison to 1909, the surface level of the central ice flows has now sunk below the level of the medial moraine, indicating a loss of at least 30-40 m (or more, if the level of the moraine itself has been lowered as well).

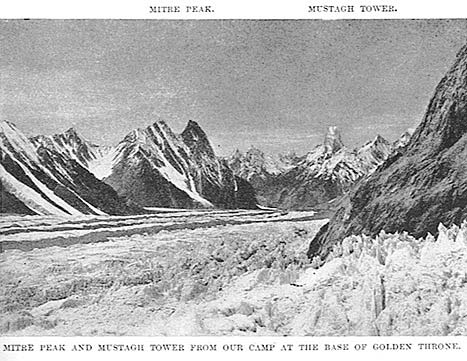

Views downvalley towards Concordia confirm this loss, as indicated by a small side glacier at the base of Mitre Peak (arrow), which had once been connected to the main body of the Upper Baltoro. As with the Lower Baltoro, the surface of the glacier also is a lot smoother than it had been in 1909.

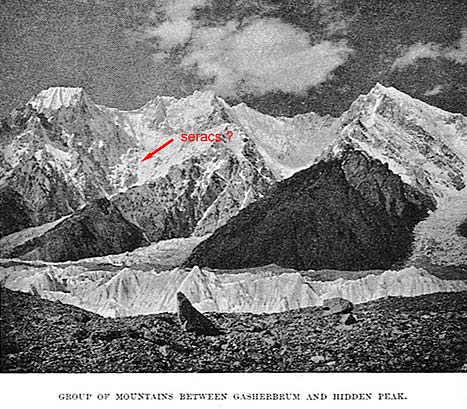

Tributary glaciers joining the Upper Baltoro from the NE (Gasherbrum V-VII) show some lowering of their surface levels. A serac barrier on the SSE-Face of "The Twins" (foresummits of Gasherbrum VII), apparently present in 1909 and casting a shadow on the wall below, has disappeared.

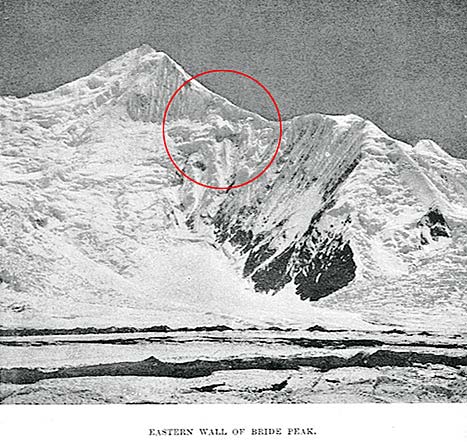

The NE-Face of Chogolisa (7668 m/25,159 ft.), which, together with the Abruzzi Glacier, feeds the Upper Baltoro, shows various signs of glacial recession. The ice flows in the central part and at the right side of the face have narrowed, sérac barriers below the North Ridge (circle) have almost vanished.

Section C: Godwin Austen Glacier and Savoia Glacier

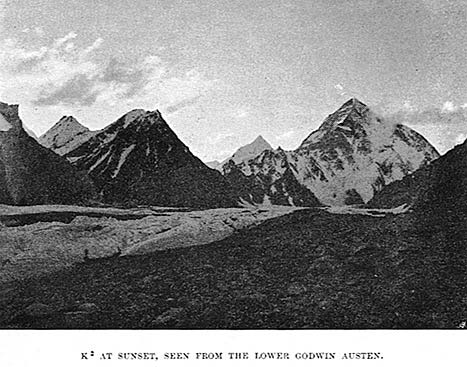

The Godwin Austen Glacier, which has its source below the southern and eastern aspects of K2 and joins the Baltoro at Concordia, has undergone similar changes as the latter. Views taken upvalley towards K2 show that the surface level of the ice flows to the left and right of the eastern medial moraine have now sunk below the level of the moraine. This again indicates a loss of at least 30-40 m.

The loss is less pronounced (in the 10-20 m range) on the Savoia Glacier, which joins the Godwin Austen Glacier south of K2. However, a western tributary of the Savoia, the Praqpa Glacier (circles), shows significant volume loss. A number of sérac barriers present in 1909 have now disappeared or been reduced in size.

Views of the Godwin Austen/Savoia confluence from the vicinity of K2 Base Camp show again the lowering and general smoothing of the glacier surface since 1909. The bulge of the Savoia Glacier left of center also appears to have decreased in volume.

Upvalley, towards Oscar Eckenstein Cwm and Skyang La, little loss is discernible along the margins of the upper Godwin Austen Glacier, although the center section shows some visible shrinkage.

Summary

Even a spot-check comparison between historical (1909) and modern (2006) images of the glaciers of the Baltoro demonstrates that glacial recession is widespread throughout the range.

The main bodies of the Baltoro and Godwin Austen Glaciers show a constant decrease of their levels, associated with a smoothing of the surface. Tributary glaciers and surrounding mountain faces equally show a loss of ice cover, often with significant changes in surface topography.

Preliminary measurements show the decrease of glacier surface levels to be in the 50 m-range, but in places probably exceeding 75m. The decrease appears to be more pronounced in the lower parts of the glaciers.

Further studies are required to confirm/disprove whether the observed recession is a gradual phenomenon or restricted to the past two decades.

| Proud Climbing Team of the Mallory & Irvine Research Expeditions: | ||